Among Winter Cranes

“Even as birds that winter on the Nile…” (Purgatorio XXIV.64)

The Quarterly of the Christian Poetics Initiative | Vol. 5 Issue 3 | Summer 2022

Getting the Angel to Speak? Poetic Constraint and Spiritual Practice

by Ben Egerton

*

Readers may be familiar with, or indeed practitioners of, ‘quiet time’. An act of setting-aside, of time away, of being apart, usually at the beginning of the day, usually with scripture. Placing a verse, or an idea, in mind, mulling over its words, wrestling, talking to God with that interior speechless voice, is a strange thing. It’s an idea seen in the life of Christ and, most notably, in the Psalms, where the psalmist frequently records his delight at meditating on God’s word.

*

Such moments, although quiet, are active. They require physical discipline: meditating, grappling, committing; it takes effort to maintain the gracious tension in which language and silence are held. But the quiet is, I think, both necessarily temporary and hard won—tempered, eventually, by the need for some kind of speech, some kind of reveal. Often, for me at least, the reveal is spoken throughout the rest of the day. How, having tried to commit something to mind (not on my knees in the morning, but often on my feet as I run), the day’s unfoldings reveal and are revealed through my earlier meditations.*

In the poem ‘Choreography’ from his 2004 collection Corpus, Michael Symmons Roberts describes Jacob wrestling the angel into speech:

I slap him. He stares at me.

Are angels speechless? This one’s

wingless, solid without weight.

Perhaps he’s trying to talk?

It could be ‘t’ or ‘c’: some stammering

Gabriel with a message?4

*

It’s tempting to read Symmons Roberts’s poem as commentary on the physicality of ‘quiet time’. However, I think there’s something in this poem to offer insight into how and where the creative practice of constraint poetry meets spiritual discipline. And it’s something more than just a relationship between poetic form and Christian language. For me, if I might be permitted to inhabit a line from Christian Wiman, “I have at times experienced in the writing of a [constraint] poem some access to a power that feels greater than I am”.5

*

To an extent, all art is born of constraint. And pursuit of spiritual practice echoes the creative writing process. Spiritual discipline is that “training or exercise […] by which we acquire practical knowledge, albeit of things of the spirit.”6 Ian Curran, his precise and diligent spiritual actions suggesting composition, talks of “inner” practice: “meditation, prayer, fasting, and study”7 that train us to be godly.8 Mary Frolich pushes further, likening our grappling with the spiritual to, she writes, “constructed expressions of human meaning”.9

*

Twelve-tone serialism is a music compositional constraint first devised by Josef Hauer in 1919, and developed by other composers such as Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. The form gives equal value to all twelve notes of the chromatic scale. And no note can be repeated until all other notes have been played. The twelve notes are first organised into a set order—the ‘tone row’. For a larger compositional ‘palette’, rows can then be reversed (retrograde), inverted, or transposed, or any combination of these. All variations of the prime row a composer constructs might run concurrently in a piece of music.10

*

Back to Curran: for prayer, perhaps read test; for fast, restrict. Back to Frolich: for constructed expressions of human meaning, read poetry. Or perhaps stick with constructed expressions.

*

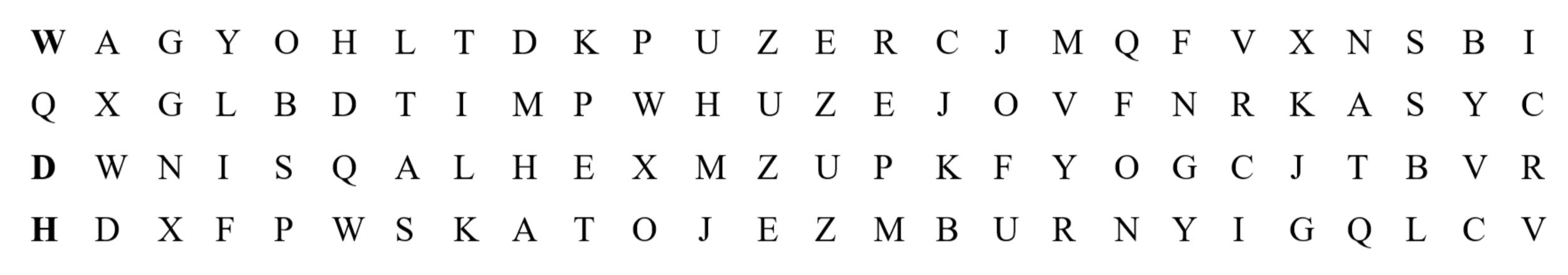

I’m currently three years and sixteen poems in on a 26-poem sequence called ‘Antiphony | Anti-phoney’. It’s composed by obeying rules derived from serial music. Rather than twelve notes of the scale, my tone row is constructed with twenty-six letters. My prime, formed at random, is:

*

Like the serialist composers, I’ve also added my own rules. For example, I can weave between rows, but letter order must be maintained; ‘Q’, ‘X’ and ‘Z’ words can begin with another letter or prefix—e.g. ‘ex’, ‘az’ ‘enq’ or ‘eq’; definite and indefinite articles, prepositions and other short constructions may be inserted as kinds of ‘passing notes’ [denoted by square brackets]. There are 102 letters in four rows, giving each poem, taking into account [additions], ≈102 words

*

To write, I have something in mind: a verse of scripture, a thought, some angel I’m wrestling. But I’m bound by the given letter order. I work along the rows, building each phrase from the available letters. I strike at, strike through, strike lucky. I try things out, practise moves and sequences. Sometimes they work. Mostly I abandon them and start again. Guided and surprised by new vocabulary and syntax, utterings begin to cohere into thoughts. And it’s my hope that these thought-poems coalesce into meditations, are records of my grapplings.

I’ve been meditating on Donne’s opening line “Thou hast made me, and shall thy work decay?” and Psalm 16, which Donne’s Holy Sonnet itself is a meditation on. My response line “his work decays” begins to form. I carry this with me for a while. Having already headed each page of a 26-page Word document with each poem’s four numbered rows, I go through each blank poem until I have ‘H’, ‘W’, and ‘D’ are available as accessible letters. Poem XIII has them as initial letters of three rows:

*

Jacob’s physical constraint was a permanent reminder of God’s blessing.13

*

There’s deep correlation between compositional constraint and spiritual quest. Perhaps, because serialism is constructed from an equal-tempered spectrum, it uses, without particular favour, the entire notational or alphabetical range. Perhaps, because serialism employs chromaticism “not occur[ing] in nature”, it speaks to something outside it.14 There’s blessing in denial. Perhaps even revelation.

*

XIII

Thou hast made me

His work decays as we—dumbstruck,

quizzical, exposed—gawp, yelp, not

expecting it. First goes our silence:

lost princess—barefoot, drenched—

hollering queasily at the looming tide

[of] work. Second: drifting loaned hymns—

I Know My Precious King Purchased Us

with His Ego—unheard against timid offertory

expectations. Mots justes erode

Zion’s underpinnings. Zeolite, zincite,

zircon: memory partly erases ‘known’

elements: faded blues, reds; umbrae;

catching japonica on yesterday’s rain.

Just [as his] voice might’ve quelled

force nines on Galilee, now Yeshua’s

faltering vocal—insolite—grows quiet,

leaches creation’s justice. Katabatic air

exhaled, negatively torch-blasting

vast swatches [of] barren cold. Vacuous rot

sets iron-hearted [in] yesterday’s collapse.

*

What is the “message” this grappling brings? In this case, I’m wondering what ‘decay’ looks like. Working with—not against—a constraint demands patience. It’s a series of deliberate moves. For, like wrestling the angel, it seldom works to approach a constraint bullishly, to knock thoughts about until they fit the “grammatical structure”.15 Rather, I must be attentive to whatever speechlessness is ‘trying’ into message. I hunch—half at prayer, half in hope—over my laptop. Like active meditation on scripture, the constraint scrutinises my thoughts, sieves them, determines their direction, ultimately accepts or rejects them.

*

Mostly, much like my prayer life, constraint writing is moments of industry interspersed with long periods of frustration, poor choreography, and silence. And so I wonder about poetic constraint as a kind of spiritual practice. Not to replace it. But as complementary discipline. Yes: meditation, devotion, listening, holding a line between said and unsaid. Why, though, is working through that puzzle of poetic constraint more rewarding? Sometimes it seems I’m better at the motions of poetry than spiritual practice. Occasionally, though, like Symmons Roberts’s Jacob, I relax just enough to listen. But the angel just stares at me. Speechless.

*

Dr. Ben Egerton

Lecturer, School of Education at Te Herenga Waka | Victoria University of Wellington

ben.egerton@vuw.ac.nz

Notes

1 Individual poems from this 81-poem sequence have been published in various journals. I exhibited the whole piece on 81 tiles as a 3m x 3m poetry installation in Tory Street Gallery, in Wellington, New Zealand, during the

LitCrawl festival in 2015.

2 Boards of Canada. Geoggadi.

Warp Records, 2002.

3 Lynskey, D. ‘Boards of Canada: Tomorrow’s Harvest—review’.

The Guardian, June 6th 2013.

4 ‘Symmons Roberts, M. ‘Choreography’.

Corpus. Cape Poetry, 2004. p.25

5 Wiman, C. ‘Gazing into the Abyss’.

The American Scholar, June 1 2007. Para. 2. Retrieved from: theamericanscholar.org/gazing-into-the-abyss/

6 Curran, M. ‘Theology as a Spiritual Discipline’.

Liturgy, Volume 26, Issue 1, 2010. p.5

7 Ibid, p.4

8 1 Timothy 4:7

9 Frolich, M. ‘Spiritual Discipline, Discipline of Spirituality: Revising Questions of Definition and Method’.

Spiritus: a Journal of Christian Spirituality, Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2001. p.71

10 For example, the tone row from Webern’s

Piano Variations, Op. 27: B, G, F#, Bb, A, G#, D, C,

Eb, C#, F, E.

There are several useful online guides for designing

a matrix, such as Robert Hutchinson’s ‘Music Theory

for the 21st-Century Classroom’ at

musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/section-195 or the

guides to serialism at Open Music Theory

(openmusictheory.com/twelvetonebasics).

11 My 26x26 matrix for ‘Antiphony | Anti-Phoney’:

12 Showing my working for ‘Antiphony | Anti-Phoney XIII’:

1) I’ve been meditating on Donne’s opening line “Thou hast

made me, and shall thy work decay?” and Psalm 16,

which Donne’s Holy Sonnet itself is a meditation on.

My response line “his work decays” begins to form.

I carry this with me for a while.

2) Having already headed each page of a 26-page Word document

with each poem’s four numbered rows, I go through each

blank poem until I have the letters ‘H’, ‘W’, and ‘D’

available as accessible letters. Poem XIII has them as

initial letters of three rows:

3) I commit to my opening phrase, and cross ‘H’, ‘W’, and ‘D’ from the rows:

His work decays

4) My next word choices are constrained by my available letters. I’m limited to words beginning with ‘Q’ (initial letter of the second row), ‘A’, ‘W’, and ‘D’. I add to the opening phrase, taking ‘[e]X’—opened up after using ‘Q’—for ‘exposed’, as per my additional rules:

His work decays as we―dumbstruck,

quizzical, exposed

5) After these eight words, the rows now look like this:

6) After trying alternatives, I take the top row ‘G’ for “gawp” to describe what “we” are doing, opening up ‘Y’ for “yelp”, and ‘N’ and ‘[e]X’, and then ‘I’ (because I’ve used ‘N’) for “it”:

His work decays as we―dumbstruck,

quizzical, exposed―gawp, yelp, not

expecting it

7) From here, it leaves the remaining letters to continue the poem—following the same process of puzzling, slotting, erasing, committing to the constraint and to my word choice—until all 102 initial letters are used and the poem reveals itself.

13 Genesis 32:25-26.

14 Covach, J. ‘The Quest of the Absolute:

Schoenberg, Hauer, and the Twelve-Tone Idea’. Black Sacred Music, 8:1, Spring 2004. p.163.

Retrieved from: hcommons.org/deposits/objects/hc:27610/datastreams/CONTENT/content?download=true

15 ‘Spiritual Discipline, Discipline of Spirituality’, p.35

Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “Momoyogusa = Flowers of a Hundred Generations.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1909. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-cb13-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Dante Aligheri. The Divine Comedy: Purgatorio. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam Dell, 2004.